|

A journey to the Bo-Kaap sheds light on the neglected history of Cape Town's signature spicy dishes.

"This is where touristy Bo-Kaap ends", says Shireen Narkedien, gesturing to the colourful walls that make the area so famous. "This is not where my tourism is. I take you to the real Bo-Kaap". Shireen has been guiding in the Western Cape since 1994, lectures on South African slave history and shares both the plots and plates that originated here centuries ago. I've long wanted to better-comprehend the Cape's unique cuisine, but somehow, the city's other iconic attractions always won favour. Table Mountain Cable Car, tick. V&A Waterfront, tick. Boulders Beach, tick.

"Apartheid is so complicated, even South African's don't understand it", Shireen continues, as we sit together inside the little Bo-Kaap Museum. "Who is a Cape Malay person? It's an Apartheid term that means nothing. A person who came from the east and practised Islam was termed Cape Malay. If you practised Christianity, you were termed a Coloured. If you came from North Africa, and practised Islam, you were a Cape Malay. Egyptians, Moroccans, and so on, were light in skin colour. They could even re-declare themselves as an Honorary White. So what is Cape Malay? Honestly, you could come from anywhere".

The building we're in, 71 Wale Street, dates back to the very era in which this term originated. In the 200 years between 1653 and 1856, 71000 slaves were captured in South East Asia by the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), or the Dutch East India Company as we know it today, and brought to the shores of Cape Town.

"When the Dutch took over the Cape Colony, they already owned many of the Eastern Colonies", Shireen explains. "Places like the Malaysian archipelago, Borneo, India, Indonesia, Java, Ceylon. They also owned parts of North and East Africa, as well as Madagascar. There they found people skilled as crafters and dealing in the spice trade. If those indigenous people dealt with any other spice traders besides the Dutch, the company would burn the fields, take them hostage and exile them to the Cape. Here in the Cape, they were stripped of their name and religion, then sold off according to their skill".

Shireen's history lesson continues as we make our way across the cobbled street. "The Afrikaans language is an amalgamation of Portuguese Creole, the San and Khoi-Khoi languages because the Dutch had to barter and trade with South Africa's indigenous people. For slaves and masters to understand each other, a mixed language emerged. Some English was then assimilated thanks to the arrival of the British, and German missionaries brought their lingo too. Then the French Huguenots arrived, seeking refuge against religious persecution". Shireen explains that this linguistic blend extends to the food too.

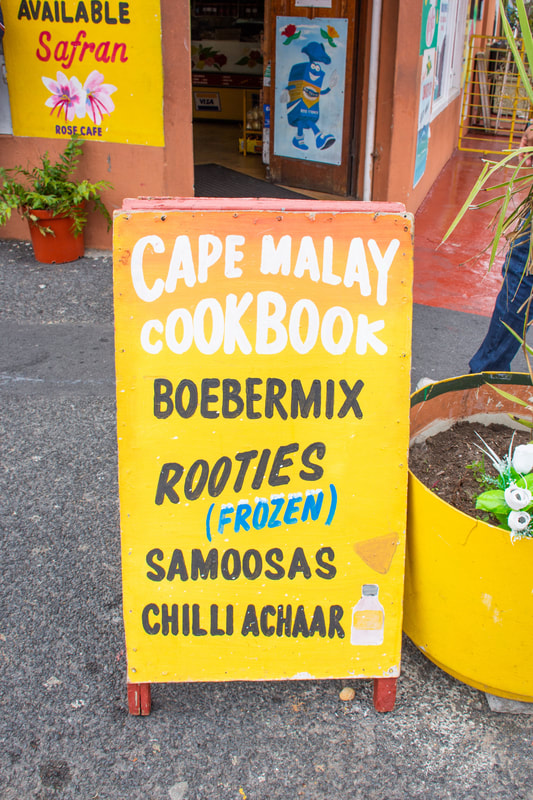

"Malaysian food is very spicy and often has a bitter taste to it. When you look at Indian food, there's a strong element of chilli. The Cape Malay slaves had to cook for the Dutch and Germans, so they simmered down their spices", Shireen says when we walk into the fragrant doors of the Atlas Trading Company. A modern monument to the continued use of spices in South African cooking today, the store stocks the entire alphabet of seasoning, from allspice to za'atar.

The Bo-Kaap is one of the oldest Muslim communities in South Africa, and although its colourful facades market South Africa to the world, it is still a regular suburb, where real people live.

"If I had to give one tip, it is to treat people with dignity and respect. For example, Friday is congregational prayer day, but often companies come to film and photograph here, bringing models. Some tourists are also climbing over walls and gates to get a photo", Shireen says when I ask about any over-tourism. She leads me then, away from the crowds on Wale Street and up to a quieter hill in the neighbourhood, where Mimoena Saunders lives with her family.

"These are the spices we use to make chicken curry, take nice heaped spoonfuls", Mimoena says, pointing to a row of bottles brimming with powders. Along with creating curry, she also shows me how to properly roll out a roti, before plopping it into a pan, where it puffs up into the perfect side. It's a scrumptious lunch, and afterwards, Mimoena, Shireen and I sip black tea together in the lounge, where I recognise a celebrity chef in a photograph hanging on the wall. You know you're in the right place for a cooking class when one Matt Preston, chef and judge of Masterchef Australia fame, shared this very table.

Inspired by Shireen's Cape annals, I visit the Slave Lodge next. Built in 1679, it's the second-oldest existing colonial structure of the Cape Colony.

In one particularly moving exhibition, a caption reads 'Meet Mr September'. As Shireen had mentioned, when slaves were brought to the Cape, they were assigned new names by their owners. The Slave Calendar exhibition highlights that it was often after the month of the year in which they landed here. It's a shock to realise that countless people I know carrying the last name October or January. After the emancipation of the Cape's captives in 1834, the freed slaves needed inexpensive homes. Perched between the mountain and the CBD, that home became the Bo-Kaap (which means 'above the Cape' in Afrikaans). It's irrefutably one of Cape Town's most historical corners and has finally been recognised as such. As of March 2019, the area now enjoys heritage protection from the City of Cape Town council.

At the end of Shireen's tour, she leaves one last provocation. "Who do you think built Cape Town? The city boasts a range of different architecture, we can see Edwardian windows and Georgian facades, but it was all crafted by slaves".

In an environment that's fast becoming a superficial social media backdrop, Shireen's challenges to conventional notions of history help me grapple with South Africa's complicated past – and present predicaments. Like the spices and dishes that survived history, many modern legacies tell the story of South Africa's often overlooked slave trade. You just have to know where to look. Understanding Cape Town's Oldest Story

Explore the Bo-Kaap with Shireen Narkedien. A registered tour guide, she coordinated the stories published in the Bo-Kaap Kitchen cookbook (Heritage Recipes and True Stories by Maggie Mouton and Craig Fraser) and can arrange tours, homecooked meals and home stays. Mail [email protected] to book.

The Slave Lodge once housed the slaves who belonged to and worked for the Dutch East India Company. Today, it’s an excellent museum that honourably engages with the torrid slavery history of the Cape Colony. Don’t miss the Slave Calendar exhibition. Open from Monday to Saturday from 9am to 5pm. slavery.iziko.org.za The Slave Church Museum on 40 Long Street is easy to miss despite being on the well-trodden tourist path. It’s one of the oldest buildings on the street and provided literacy training and Bible classes to freed slaves. Open Monday to Friday from 9am to 4pm. The Grand Daddy Boutique Hotel makes a great base and is within walking distance of all activities mentioned (and right next door to the Slave Church Museum). The proudly South African hotel is also a heritage building and has been operating as a boutique hotel for over 120 years. granddaddy.co.za

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed