|

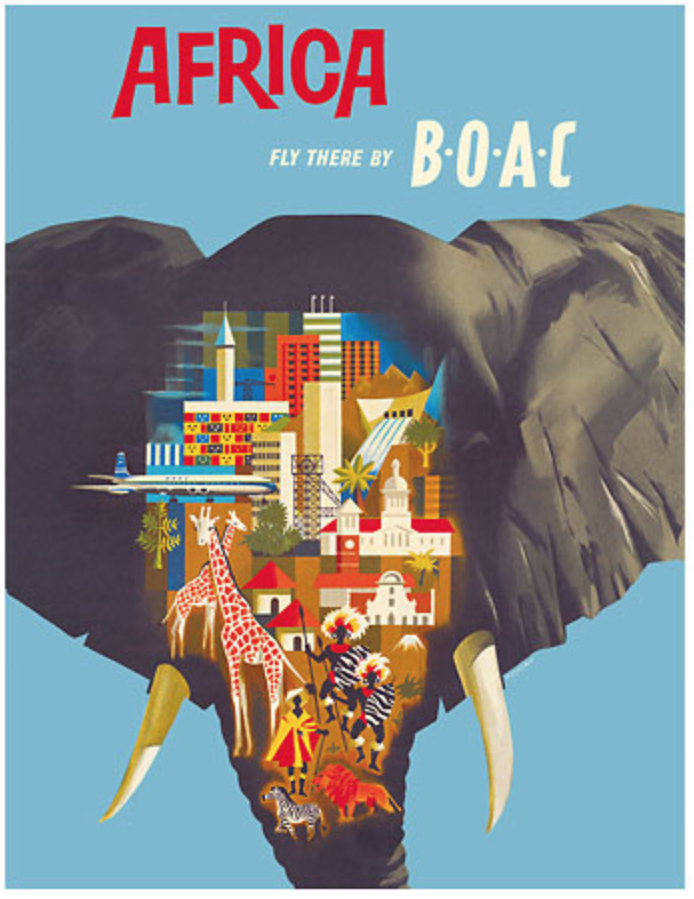

With a map of Botswana open in front of us my family and I pore over a long strip of black tar tagged the A3 that stretches across the country from Francistown in the east to the blue puddle of the Okavango Delta in the west. Growing up, my sister Shelby and I were always in charge of navigation, keeping us keenly aware of our route so we knew which dorpies we passed through, which were worth stopping at for homemade rusks and which to skip in favour of an old pass instead. We’ve covered this particular highway route before as a family, but always made the mistake of sprinting past the big network of salt pans, including the Makgadikgadi and Nxai, towards the greener views of Maun. This time, we turned off the tar because of a century-old watercolour. We all sit under a mighty mowana, my father, mother and I, overlooking a wrinkled salt pan in Nxai Pan National Park. Our oasis is an enormous arboreal beast known to most as the baobab, known in Botswana as a mowana. Our mission to see the Nxai Pan National park for the first time was born because we wished to find this exact frame of Baines’ Baobabs. Google images shows many baobab sketches that Baines had put to paper in his lifetime (I stumbled across at least 20), but finding the painting of this particular oasis on the edge of Kudiakam Pan was an elusive battle. And it led to a serious bout of mowana mania. After a number of emails to art auctioneers and a visit to the Museum Africa in Johannesburg, the original baobab painting turned up in the Royal Geographic Society’s archives. And here we are. A small crew travelling across Southern Africa like those intrepid explorers did, settling in under a mowana. The seven trees haven’t aged and seem fixed in the era in which Baines had first seen them over a century ago. Surrounded by the purple stains of sunset, craggy branches reach into the sky with defiance and the scene captured on paper comes alive in a heart-wrenching show that stays true to Baines painting. It feels like ancient souls live inside these trees, stubbornly unobtainable and yet comforting to be around. Thomas Baines was a British landscape painter who came to South Africa in the 1850s as an artist of war to depict battles in Bloemfontein, but later turned to painting vivid watercolours of nature in Southern Africa. Talented enough for the Royal Geographic Society to commission him, Baines accompanied David Livingstone on the second expedition to Victoria Falls to paint the first visual evidence of the Smoke that Thunders. Leaving South Africa in the 1860s, the intrepid contingent passed through Botswana’s Kalahari and they were drawn to a clump of seven gigantic baobabs surrounded by a seemingly infinite salt pan. And who could blame them? Shade and shelter beckoned from kilometres away, and on arrival Baines immortalised this setting in his watercolour, signing it, ‘A group of Baobab trees on the north west spruit of the Mtwetwe pans, May 1862’. Today, it lives in the archives of the Royal Geographic Society many kilometres away in England. Like Baines’ Baobabs, Botswana remains relatively untouched, a land of extremes and immense biodiversity that includes this odd-looking plant that’s more towering succulent than leafy tree. It’s one of the most authentic wilderness destinations and especially accessible for South African travellers. Dominated by a parched desert interior and flanked by wet floodplains in the east (now officially a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and a mighty river system to the north, more than 45 percent of the land in Botswana is protected. The government strives for strong conservation policies, reimbursing citizens for livestock and farm produce damaged, eaten or trampled by wandering elephant, lion and wild dog, in an effort to safeguard both human and animal livelihood. And with a relatively small population of about two million, there’s little need for damaging urban expansion. This means tourism is big. And among the many drawcards are the baobabs. Our mowana meander as we’ve dubbed it, was born of the mystery of Baines’ picture, as well as a craving for remarkable detours. In the search for the scene of the painting, other upside-down trees came to light in Botswana, in places my family and I had never bothered to look until now. Take Kasane, for instance. It’s a small town in the country’s far north and there’s a real Wild West feel about it, where dogs chase warthogs down the dusty streets. The baobab takes about half an hour to visit if in the area exploring Chobe National Park or on the way to Victoria Falls. Outside the police station is a broad-bellied baobab which served as a colonial-era jail cell. In southern Botswana near Gweta are two more famous specimens: Chapman’s and Green’s Baobabs. These remote trees on the fringe of the world’s largest network of salt pans were historically used as stopovers by traders, hunters and missionaries. Driving through the Mopane veld, past Gweta village, countless kraals and the odd set of elephant foot prints, you can spot these mowanas from a good distance. Green’s Baobab is the first tree on the route, but it’s Chapman’s tree that wins admiration. A big game hunter in the 1860s, James Chapman owned one of the first cameras in Southern Africa and joined Baines and Livingstone on their trip to the Victoria Falls. He never shared Baines’s fame as his photographic equipment seized in the moist forested area, but he still gained mowana mogul status, sharing his name with the 500-year-old tree on the outskirts of Ntwetwe Pan. The baobab is riddled with bullet holes and messages left by travellers who used its trunk as a post office. See Botswana's BaobabsStill, Baines’ Baobabs are the most remarkable. Sitting at the campsite across from them, I scan the pans. I realise I’ve learnt another important travel lesson from my parents: if the road you pick is so honest and captivating it makes your body ache with contentment, you should choose it again. And never stop searching for beauty, even if you have to go back a hundred years to find it. Visit the Kasane Prison Baobab Postal Tree (Police station number tel +2676252444). It’s on the main road between the A33 turn-off and Chobe National Park – there’s only one tarred street and it’s easy to find. Stop at the waterhole at Elephant Sands Lodge for lunch, on your way south towards the pans, and hold thumbs for a close-up elephant sighting. Make time for a three-hour return trip to Chapman’s and Green’s Baobabs about 11km from Gweta Village they are remote, and a 4×4 is required. You’ll also need a Tracks4Africa navigation system or an exceptionally detailed map. It’s unlikely you’ll find other vehicles in that vast tract of wilderness. Skirt the edge of the Makgadikgadi salt pans (pack some padkos) on the way back to the A3. Pull in for a look around Planet Baobab. Even if you don’t spend a night, the afro-funk decor is charming, there’s cold beer at the quirky bar and the toasted sarmies are great if you’re okay with African time. Visit Baines’ Baobabs in Nxai Pan National Park (xomaesites.com, tel +2676862221), but get there early if it’s a day trip so you can include a drive to South Camp’s waterhole for great game sightings keep your eyes peeled for wild dog. If you have time, include an overnight camping stay at Kubu Island(we couldn’t fit it into our trip, but it could be your first stop on the mowana meander from the south). South Africans don’t need a visa to visit Botswana, but if you’re entering by car you’ll need to pay taxes and border fees in pula at the border. Have at least P200 a vehicle. Leave dairy and meat at home because food regulations restrict imported supplies and vehicle checks are made. Pack water, firewood, loo paper and anything else you’ll need for camping at Baines’ Baobabs. There’s a pit loo and a fire slab, but that’s about it. Watch out for animals crossing the A33. This story first appeared in Getaway Magazine.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed